Tech's Toxic Trail: Confronting E-Waste in Southeast Asia

- Simon Kaack

- Apr 22, 2024

- 4 min read

Everyone is happy about a new electronic device, especially if it looks better, works faster, and is advertised as less-energy-consuming. But what if all these promises only apply for as long as the product is in use? The rapid consumption of electronic goods has given rise to a less discussed but critically important issue: electronic waste, or e-waste.

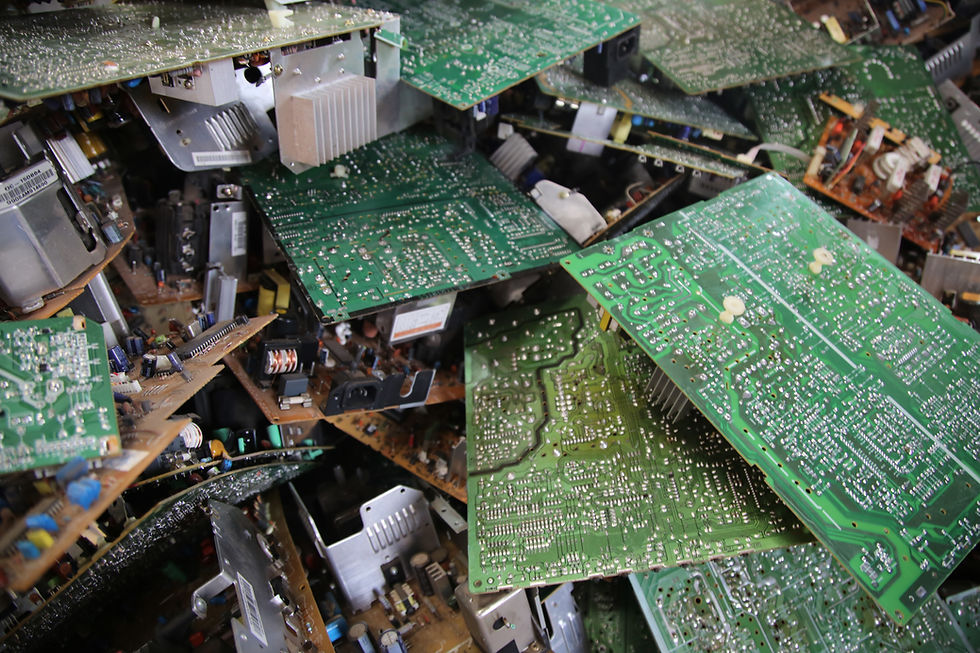

E-waste refers to discarded electronic appliances and gadgets that are no longer wanted, working, or in their usable life cycle. This includes a wide range of products – from consumer electronics like mobile phones and computers to larger household and industrial appliances. The problem with e-waste lies not just in its sheer volume but also in the hazardous materials it contains, such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, which can pose significant environmental and health risks if not properly managed.

The statistics on e-waste are staggering and paint a grim picture of the scale of this issue. According to the Global E-waste Monitor, millions of tonnes of e-waste are generated worldwide each year, and only a fraction of this is recycled properly. The rest ends up in landfills or is informally recycled, often in ways that harm the environment and human health, especially in countries with inadequate waste management systems.

The improper disposal and informal recycling of e-waste can lead to severe environmental degradation. Harmful chemicals can leach into the soil and water, contaminating food chains and water supplies. Additionally, the burning of e-waste to extract metals releases toxic fumes into the air, posing serious health risks to nearby communities, particularly in developing countries where much of the world's e-waste is shipped for processing.

In Southeast Asia, the rapid proliferation of electronic devices, coupled with escalating consumption rates, has positioned e-waste as a critical environmental issue. The region's e-waste dilemma is exacerbated by its role as both a producer and a recipient of global e-waste, compounded by varying levels of regulatory frameworks and waste management infrastructure across its countries. The e-waste management challenge in Southeast Asia is not just about dealing with local waste. The region also grapples with the importation of e-waste from developed countries, often processed under hazardous conditions, posing significant environmental and health risks to local communities and ecosystems.

The shift of e-waste dumping grounds from China to Southeast Asia, following China's e-waste import ban in 2017, underscores a global dynamic where affluent nations offload their electronic waste onto less wealthy counterparts. This transfer not only burdens the receiving nations with environmental and health hazards, particularly for workers in informal e-waste recycling sectors and communities residing near e-waste processing sites. Subsequently, it raises ethical questions about global waste management practices.

The allure of the latest tech gadgets has led to a surge in e-waste, with consumers discarding old models at an alarming rate. Illegal imports have transformed parts of the region into e-waste dumping grounds. Thailand, for example, has seen its e-waste industry balloon over the past six years, with a staggering 56,154 metric tons of e-waste imported in just the first 10 months of 2023.

The e-waste crisis is exacerbated by a lag in regulations and public awareness. Despite a ban on importing over 400 types of e-waste, Thailand and its neighbors struggle to control the influx and ensure safe processing. The situation is complicated by the growth of e-waste processing industries, particularly in Thailand's Eastern Economic Corridor, where the surge in factories has not been matched with stringent oversight. Many of these facilities lack the proper permits, raising concerns about their environmental and health impacts.

Many of these illegal activities are driven by the high demand for valuable recyclable materials found in discarded electronics, such as copper and gold. The environmental and health consequences of such practices are severe, as improper disposal methods lead to toxic chemicals leaching into the soil and waterways, posing significant risks to local communities.

To contain the crisis, work needs to be done on various fronts. Manufacturers should be encouraged or mandated to take back their products at the end of their life cycle for proper recycling or disposal. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies can incentivize manufacturers to design products that are easier to recycle and have a longer lifespan. Encouraging innovation in the design of electronic products can lead to more sustainable solutions, such as modular designs that allow for easy repair or upgrading, thereby extending the product's lifespan and reducing waste.

Therefore, stronger regulations and international agreements are needed to prevent the export of e-waste to countries with inadequate disposal facilities. Enforcing stricter standards for e-waste management can drive better practices throughout the lifecycle of electronic products. Countries in Southeast Asia need to develop and enforce robust e-waste management regulations. Legislation should not only address the proper disposal and recycling of e-waste but also regulate the import and export of electronic waste to prevent illegal dumping.

Additionally, investing in formal e-waste recycling facilities can provide safe and environmentally sound alternatives to informal recycling. Enhancing e-waste recycling infrastructure and technologies can maximize the recovery of valuable materials and reduce the need for virgin resources. This not only mitigates environmental harm but also offers economic benefits by creating jobs in the recycling sector.

Moreover, educating consumers about the importance of responsible e-waste disposal and the availability of recycling programs is crucial. Opting for products with a longer lifespan and practicing the 'reduce, reuse, recycle' mantra can make a significant difference.

The e-waste crisis in Southeast Asia is a ticking time bomb, demanding urgent action on multiple fronts. It's a stark reminder of the hidden costs of our digital age, urging us to reconsider our relationship with technology and its lifecycle. Therefore, when buying an electrical product, it makes sense to not only appreciate its shiny new condition but also to ask where the individual parts of the appliance will end up when it is no longer in use.

Comments